Introduction to Collision Regulations - Is there a risk of Collision?

Caution:

- The following information has been simplified so we can give you a basic introduction using (mostly) non-technical language. Review the actual Regulations for in-depth information (we have noted the rule number, in square brackets, where practical). The Regulations can be found on our links page.

- A lot of effort has been made to ensure the information is correct, but errors may occur (If you find one please leave a message for our Webmaster).

- This information is intended for boaters on the BC Coast; it does not address modifications for vessels operating in the Great Lakes Basin.

- These diagrams are not to scale. To allow both vessels to be seen in the graphic, they have been moved much closer together than is safe in the real world.

- For simplicity, these situations are very basic, and are for vessels within sight of each other (seeing a vessel only on radar is not considered in sight). The section on Restricted Visibility covers what to do in those conditions.

Before talking about ways to assess collision, we must touch on look-out [Rule 5] and safe speed [Rule 6]. Obviously we can't assess a collision risk if a proper look-out is not maintained (that includes sound as well as sight). Safe speed is also a major factor in being able to assess risk of collision and in avoiding collisions. A vessel running at high speed through the pleasure craft fishing fleet off the hump has very little time to assess risk of collision with individual vessels. (Another aspect of this situation is found in the Canadian Modifications to the Rules, which require vessels to ensure their wash does not "adversely affect" another vessel.)

The primary visual method of determining risk of collision is the change in "Relative Bearing" - which means the bearing of another vessel, relative to the course your vessel is on, over time. Sounds complicated, but it is something you do every day while driving, when gauging if the car approaching the intersection from the side will get there before you, or walking through the mall when approaching another person walking in a different direction. Note that this method only works if both vessels are maintaining a constant course and speed (or constant rate of course change and/or speed).

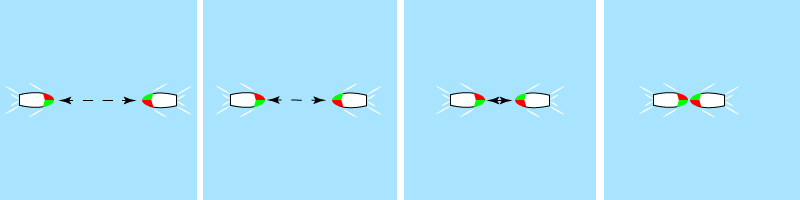

In the first case there are two vessels heading straight at each other, what the Collision Regulations refer to as a "Head-On" situation. The relative bearing, as shown by the dashed line is not changing as they approach. There is a high risk of collision if they both keep going.

In our second case, two vessels are in what the Collision Regulations term a "Crossing Situation". Again there is no change in relative bearing, as shown by the dashed line. Another high risk of collision.

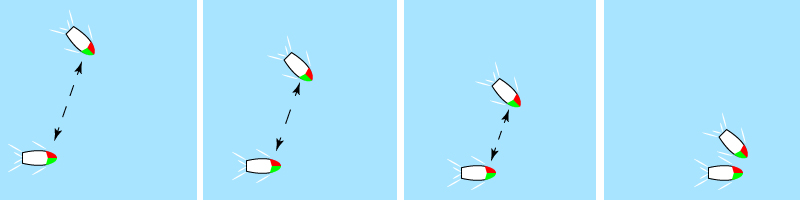

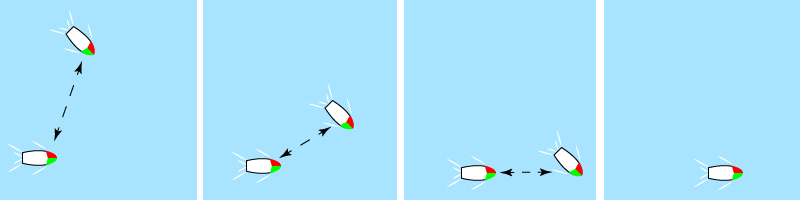

In our third case, the two vessels are again in a Crossing situation, and are starting in the same relative positions as the last case. However, this time, the upper vessel is going faster. As time goes on, the relative bearing is changing fairly quickly. There is no risk of collision if both vessels maintain their course and speed. (again, this diagram is not to scale. To fit into each panel, vessels have been put much closer together than is safe.) If the relative bearing shifts aft, rather than forward, the other vessel will pass astern of us.

Relative bearing can be determined in a number of ways.

- If your vessel is maintaining a steady course, from a fixed location on your boat, observe the other vessel relative to some fixed object on your boat. For example, from your position at the helm, if the other vessel is in line with one of your stanchions, or a window frame, or a cleat, etc. you can determine change in relative bearing by seeing if the other vessel stays in line with your stanchion or other object as it approaches. If it does, or moves very slowly one way or the other, there is no, or little, change in relative bearing, so there is a risk of collision.

- If the other vessel doesn't quite line up with a fixed point on your boat, you can extend your hand and see if you can fill the gap between the two with your fist or some fingers. Or you can do the same sort of thing with a ruler or even the tips of your dividers.

- You may use a compass to take bearings. If the compass bearing does not change, the relative bearing is not changing. (Using a compass may work much better if you are unable to steer a very steady course.)

- Radar bearings may also be used, but be aware of the limitations taking a bearing with radar.

Note that when evaluating risk of collision for a large vessel, or tow, even if the bearing is changing, risk of collision may still exist [Rule 7 d(ii)]. (As a large ship gets closer, the arc of bearing between bow and stern gets larger. The same happens with a tug and tow. So the bearing to the tug, for example, will change even though a bearing through the centre point between tug and tow remains the same.)

Under the Collision Regulations, if there is any doubt about whether risk of collision exists, it is deemed to exist [Rule 7 a]

Return to Basic Introduction to the Collision Regulations